Post-Mortem: A Disastrous Git Merge and the Resulting Workflow

A detailed breakdown of a force-push incident that deleted two days of work, and the strict git branching policies established in the aftermath.

Incident Summary

Date: 2025-03-14

Duration of impact: ~6 hours

Commits lost: 48 across 3 contributors

Recovery time: 12 engineering-hours

Root cause: Unprotected main branch combined with git push --force

I'm writing this up partly because our team agreed we should document what happened, and partly because I keep thinking about it and figure I should put it somewhere other than my head.

What happened

On a Friday — because it's always a Friday — one of our junior developers was stuck on a merge conflict inside a long-running refactoring branch. The kind of conflict where Git marks up half the file and nothing looks right no matter how you read the diff markers. He'd been at it for a while. Tried resolving manually, got confused, tried again. Eventually, somehow, he ran git push origin main --force.

I still don't fully understand the sequence of events that led to that exact command. I've asked about it a couple of times, and the answer is always some version of "I was trying things from Stack Overflow." Which. Yeah. I've been there. We've all pasted commands we didn't fully understand into a terminal at 4pm on a Friday. I won't pretend otherwise.

On any other week, branch protection rules on main would have stopped it cold. GitHub would have rejected the push, thrown an error, end of story. But we'd been in the middle of migrating the repo from our old GitHub org to a new one earlier that week. During the migration, branch protection got turned off. Somebody was supposed to re-enable it. Nobody did. There was no ticket for it. No checklist item. It just... fell through.

So the remote accepted the force push. Forty-eight commits from three different developers. Two days of integrated, reviewed, tested work. Gone from main. Replaced with whatever was on this junior dev's local branch, which was weeks behind.

He didn't even realize what had happened. He pinged me on Slack about twenty minutes later asking why his PR was showing weird diffs. That's when I looked at the commit log and felt my stomach drop.

The recovery

The next few hours were not great.

Here's the thing about git push --force — it doesn't delete commits from the server immediately. Git's garbage collection hasn't run yet, the objects are still there, they're just orphaned. No branch points to them anymore. They're floating. If you can find them, you can get them back. If.

We SSH'd into our CI server, which had fetched main recently, and ran git reflog to find the commit hash that main was pointing to before the force push landed.

git reflog show origin/main

That gave us a list. We found the hash. Then we did a hard reset on a recovery branch:

git checkout -b recovery-main

git reset --hard abc123f

And then came the tedious part — comparing the recovered branch against what was now on main, making sure nothing was missing, cherry-picking the handful of commits that had landed between the last CI fetch and the force push.

git log --oneline recovery-main..main

git cherry-pick d4e5f6a

git cherry-pick 7b8c9d0

It worked. We got everything back. But it took the rest of the afternoon and part of the evening, and there was about a two-hour window where none of us were sure we'd recover all of it. One of the developers whose work was overwritten had already gone home for the day. We had to call him to ask if he had any local branches that might have commits we couldn't find on the server.

He did, thankfully. One commit that existed only on his laptop.

That moment — sitting in a conference room at 7pm, waiting for someone to confirm over the phone that yes, he still had the branch locally — was when the stress really hit. Not the initial "oh no" of discovering the force push. That was more like shock. The real weight came later, in the quiet parts, when you're just waiting and hoping.

The first thing we changed

The obvious one. Branch protection went back on main within the hour. But more than that — we wrote a post-migration checklist and stuck it in our runbook. Any time we touch repo settings, org transfers, anything administrative, someone has to verify protection rules as the last step. Two people sign off.

It's the kind of process that feels like overkill until you remember why it exists.

We also set up a Slack alert that fires if branch protection is disabled on any repo in our org. That one took about fifteen minutes to configure through GitHub webhooks. Should have had it from the start. Didn't even occur to us.

{

"events": ["branch_protection_rule"],

"config": {

"url": "https://hooks.slack.com/services/xxx/yyy/zzz",

"content_type": "json"

}

}

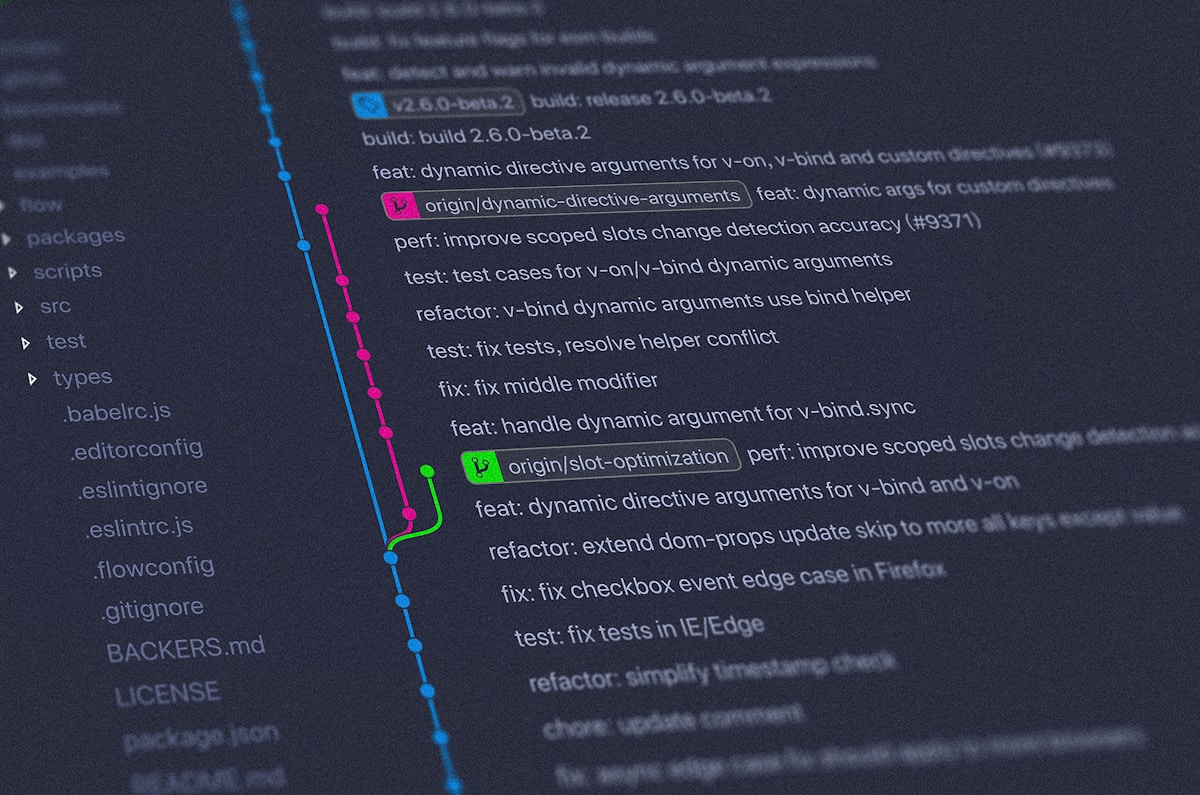

How we think about branches now

Before the incident, our branching was... informal. People made branches. Sometimes they were named well, sometimes they were called fix-stuff or anurag-temp. There was no convention. Developers would rebase against main when they felt like it, or merge main into their branch, or sometimes just work off main directly for small fixes.

None of that was technically wrong. It worked fine when the team was three people who sat next to each other. But the team had grown to seven by the time the incident happened, and the informal approach was already creaking.

After the incident, we introduced naming conventions. Every branch starts with a prefix:

git checkout main

git pull origin main

git checkout -b feat/payment-gateway-retry

feat/ for features. fix/ for bug fixes. chore/ for dependency updates, CI changes, that kind of thing. hotfix/ for production emergencies.

I was skeptical of this at first, honestly. It felt bureaucratic. But it turns out that when you're scanning a list of 30 active branches on GitHub, knowing at a glance which ones are features vs. fixes vs. maintenance work is genuinely useful. It also helps with automation — our CI pipeline runs different checks depending on the prefix.

The bigger change was how we handle keeping branches up to date with main. We settled on local rebasing. When your feature branch falls behind, you rebase:

git fetch origin

git rebase origin/main

Not git merge origin/main into your branch. The merge approach works, technically, but it creates these merge bubbles in the history that make git log and git blame harder to read later. With rebase, your feature branch looks like it was started from the current tip of main, even if it's been in progress for a week.

The tradeoff is that rebasing rewrites your local commit history. Which means pushing to the remote requires a force push. And given what had just happened, the words "force push" made people flinch.

The force-with-lease compromise

This is where we spent the most time arguing, actually.

One camp wanted to ban force pushing entirely. Just disable it across the org. If your branch has diverged, delete it and re-create it. Clean and safe.

The other camp — which I was in — thought that was too heavy-handed. Rebasing is a useful workflow. The problem wasn't force pushing per se. The problem was force pushing to main, on a branch that other people depend on, without checking whether you're about to overwrite someone else's work.

We compromised on --force-with-lease. It's a flag that tells Git to check whether the remote branch has been updated since your last fetch. If someone else pushed commits to the branch after you last fetched, the push is rejected.

git push origin feat/payment-gateway-retry --force-with-lease

It's not foolproof. If you do a git fetch right before pushing, --force-with-lease will happily let you overwrite whatever was fetched, because from Git's perspective, you're "up to date." But it catches the most common accidental case — where you rebase locally and push without realizing a teammate pushed to the same branch an hour ago.

We also set up a Git alias so people don't have to type --force-with-lease every time:

git config --global alias.pushfl "push --force-with-lease"

Now git pushfl origin feat/whatever does the right thing. Some of the team uses it, some still types out the full flag. Doesn't matter, as long as bare --force isn't in anyone's muscle memory anymore.

And --force on main or develop? Blocked at the GitHub level. Can't do it even if you try. That's the non-negotiable part.

Cleaning up before merge

This was a smaller change but one that I personally care about more than I probably should.

Before the incident, our main branch history was a mess. Commits like WIP, fix, fix again, okay actually fix, linting, forgot to save. You'd open git log and it read like someone's internal monologue during a debugging session.

We now ask everyone to clean up their commits before opening a PR. Interactive rebase:

git rebase -i HEAD~5

That opens your editor with the last 5 commits listed. You can squash them together, reword them, reorder them. The goal is to end up with one or two commits per feature that actually describe what the change does.

A good commit message, for us, looks something like:

feat: add retry logic to payment gateway

Previously, failed payment attempts returned a 500 to the user

immediately. This adds exponential backoff with 3 retries before

giving up. Timeout per attempt: 5s.

Closes #247

Not everyone follows this perfectly. Some PRs still land with mediocre messages. I've decided that's fine. The point isn't perfection — it's that main should be readable six months from now when someone is trying to figure out why the payment retry logic works the way it does.

Automation that actually stuck

After the initial rush of policy changes, we also added some tooling. Some of it stuck. Some of it didn't.

What stuck: pre-commit hooks via Husky. Every time you run git commit, a hook fires that runs ESLint and Prettier on the staged files.

{

"lint-staged": {

"*.{js,ts,tsx}": ["eslint --fix", "prettier --write"],

"*.{css,scss}": ["prettier --write"]

}

}

If linting fails, the commit is blocked. This was annoying for about two weeks while everyone adjusted their editor configs to match. Now nobody notices it. It just runs.

What also stuck: a prepare-commit-msg hook that prepends the branch prefix to the commit message automatically. If you're on feat/payment-retry, your commit message gets feat: added to the front. Small thing, but it means even lazy commit messages end up categorized.

What didn't stick: we tried requiring commit message linting with commitlint, enforcing the conventional commits spec down to the character. The team hated it. People would write perfectly reasonable commit messages that got rejected because they used a capital letter after the colon, or because the subject line was 73 characters instead of 72. We kept it for two months and then quietly removed it. The spirit of the rule was right — write clear commit messages — but the enforcement was too rigid.

I go back and forth on whether removing it was the right call. Some of the commit messages have drifted back toward vague territory. But nobody's actively fighting the tooling anymore, which is probably worth more in the long run.

What I'd tell someone setting this up from scratch

Don't wait for the incident.

That's the most honest thing I can say. We could have had branch protection enabled from day one. We could have had naming conventions. We could have had --force-with-lease as a standard practice. None of this is advanced Git knowledge. It's in the docs. It's in every "Git best practices" article ever written.

But we didn't do it because things were working fine. The team was small. Everyone knew what everyone else was working on. The informal approach felt adequate. And it was, right up until it wasn't.

The second thing I'd say: be careful about over-correcting after an incident. The temptation is to lock everything down, add process to every step, make it impossible for anything bad to happen ever again. But too much friction and people start finding workarounds. They'll push to a personal fork and PR from there, or they'll stop making small frequent commits because the commit hooks are too slow, or they'll just ignore the conventions because nobody's enforcing them and the automation is annoying.

We tried to find the middle ground. Protect the things that matter — main, production branches. Automate the stuff that's easy to automate — linting, formatting. Set conventions for the rest — branch naming, commit messages — but don't die on every hill.

Where we are now

It's been about ten months since the incident. We've merged somewhere around 2,000 PRs since then. No force pushes have escaped a feature branch. No work has been lost. The workflow runs smoothly for the most part.

But I'm not going to pretend everything is settled. We still debate whether the rebase-only policy is too strict. Some developers, especially ones who join from teams that used merge workflows, find it confusing. Rebasing rewrites history, which means your local branch and the remote branch diverge, which means you need --force-with-lease, which means you need to understand what that flag does and why bare --force is banned. That's a lot of context for someone who just wants to push their code.

A couple of people have asked whether we should just allow merge commits from main into feature branches and avoid the whole rebase dance. I don't have a great answer. The history is cleaner with rebase. But "cleaner history" is an aesthetic preference as much as a practical one, and I'm not sure it's worth the learning curve and the anxiety around force pushing.

We also haven't fully solved the problem of long-lived feature branches. When a branch is open for two weeks, rebasing against main every day or two becomes a chore. Conflicts accumulate. Sometimes you resolve the same conflict three times in a week because main keeps moving. There are strategies for this — feature flags, trunk-based development, smaller PRs — but we haven't committed to any of them. We just sort of muddle through on a case-by-case basis.

And honestly, some of the policies we put in place were emotional reactions to a bad day. I recognize that. The question of how much process is the right amount of process doesn't have a clean answer, and it shifts as the team changes. Someone leaves, someone new joins, the codebase grows, the deployment pipeline changes. The rules we wrote ten months ago might not be the right rules a year from now.

We still talk about it, though. That's probably the best thing that came out of the incident — the team actually discusses how we work with Git, instead of everyone just doing whatever they learned five years ago and hoping it works out. Whether our specific rules are optimal, I genuinely don't know. But the fact that we have rules, and that people understand why they exist, feels like it matters.

The junior dev who ran the force push is still on the team, by the way. He's one of the more careful committers now. Runs git status and git log before every push. Probably more careful than he needs to be, but I get it.

I still check that branch protection is enabled more often than is strictly rational.

Written by

Anurag Sinha

Developer who writes about the stuff I actually use day-to-day. If I got something wrong, let me know.

Found this useful?

Share it with someone who might find it helpful too.

Comments

Loading comments...

Related Articles

The 5 Rules of Git Branching for High-Velocity Teams

Practical constraints for code integration that actually work. Less about naming conventions, more about not breaking production.

Monolith vs. Microservices: How We Made the Decision

Our team's actual decision-making process for whether to break up a Rails monolith. Spoiler: we didn't go full microservices.

An Interview with an Exhausted Redis Node

I sat down with our caching server to talk about cache stampedes, missing TTLs, and the things backend developers keep getting wrong.